Jerri-Lynn here. For more detail on the carnage in the oil and gas sector, see also the NY Times front page story I linked to today, Fracking Firms Fail, Rewarding Executives and Raising Climate Fears. We’ve been tracking this bust in crossposts, and have featured the excellent series at DesmogBlog on fracking’s follies. The day of reckoning has arrived, and Wolf Richter’s post highlights the record number of bankruptcy filings in this banner year.

By Wolf Richter, editor of Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street

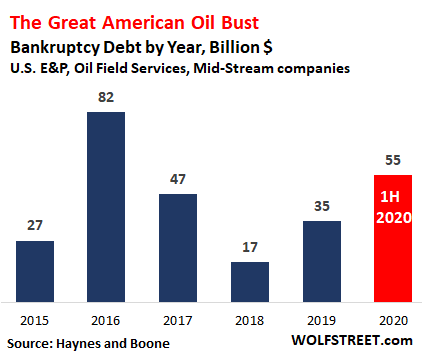

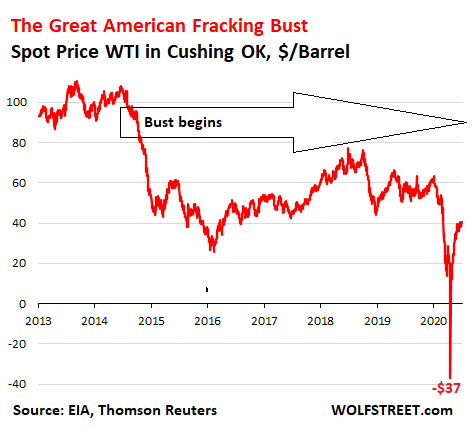

The Great American Oil Bust started in mid-2014, when the price of crude-oil benchmark WTI began its long decline from over $100 a barrel to, briefly, minus -$37 a barrel in April 2020. Bankruptcies of US companies in the oil and gas sector started piling up in 2015. In 2016, the total amount of debt listed in these filings hit $82 billion. Bankruptcy filings continued, with smaller dollar amounts of debt involved. In 2019, the shakeout got rougher.

And this year promises to be a banner year, as larger oil-and-gas companies with billions of dollars in debt collapsed, after having wobbled through the prior years of the oil bust.

The 44 bankruptcy filings in the first half of 2020 among US exploration and production companies (E&P), oilfield services companies (OFS), and “midstream” companies (gather, transport, process, and store oil and natural gas) involved $55 billion in debts, according to data compiled by law firm Haynes and Boone. This first-half total beat all prior full-year totals of the Great American Oil Bust except the full-year total of 2016:

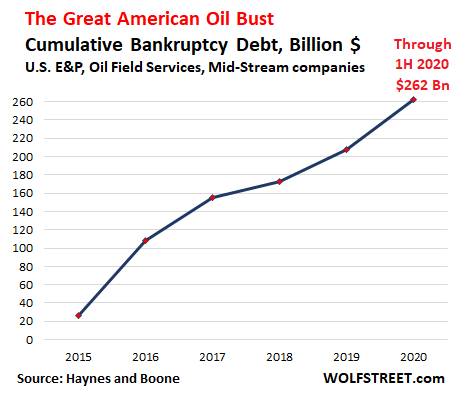

The cumulative amount of secured and unsecured debts that the 446 US oil and gas companies disclosed in their bankruptcy filings from January 2015 through June 2020 jumped to $262 billion:

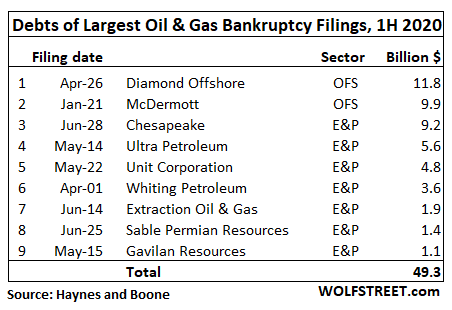

The three biggies: In the first half of 2020, nine of the 44 US oil and gas companies that filed for bankruptcy listed over $1 billion in debts, including the three biggies with debts ranging from $9 billion to nearly $12 billion, according to data by Haynes and Boone.

These three companies – oil-field services companies Diamond Offshore and McDermott and natural-gas fracking pioneer Chesapeake – are the biggest in terms of debts that have toppled in the Great American Oil Bust so far. Those three companies combined listed $31 billion in debts, accounting for 56% of the $55 billion in total debts listed by all 44 companies to file so far this year:

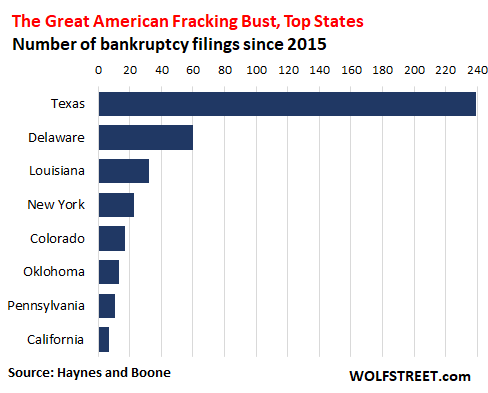

Bankruptcy Epicenter is in Texas.

Since 2015, there have been 239 bankruptcy filings by oil-and-gas companies in Texas – the largest oil producing state in the US – of the 446 total US filings. So far this year, Texas accounts for 39 filings of the 44 total filings in the US.

Of note, Chesapeake is headquartered in Oklahoma, but it filed in U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of Texas and counts as a Texas bankruptcy.

Delaware’s major industry is not oil and gas, but coddling corporations, and many oil-and-gas companies are incorporated in Delaware and they’re filing for bankruptcy in Delaware – hence the state’s second place among states with the most oil-and-gas bankruptcy filings since 2015:

The Price-Collapse of Crude Oil and Natural Gas.

The Great American Fracking Bust took on absurd proportions when the price of WTI in the futures market plunged to minus -$36.98 on April 20, 2020, in an epic WTF moment for the entire oil industry. Since then, the price has bounced off and currently trades just over $40 a barrel, where the US fracking industry is still burning large amounts of cash:

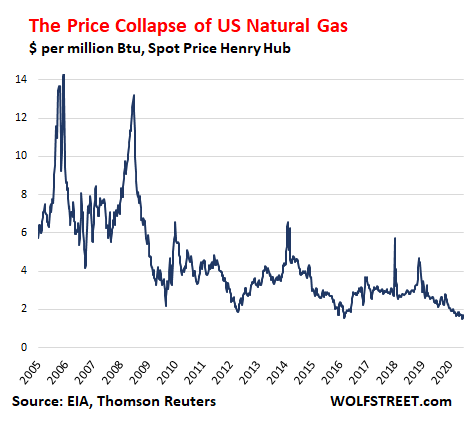

Fracking has turned the US into the world’s largest producer of natural gas. The flow of cash into this sector has been epic. Chesapeake was on the forefront here, both in terms of boosting natural gas production and in terms of bamboozling investors into handing over billions of dollars that it then efficiently burned year after year.

The ensuing natural-gas glut has crushed the price of natural gas – despite enormous efforts and investments to export natural gas via pipelines to Mexico and via LNG export terminals to the rest of the world. But whenever there was new demand, it was out-powered by higher production as the cash kept pouring in, and the price continued to fall, currently at $1.83 per million Btu:

There have been side effects too. The crushed price of natural gas – plus the arrival in the 1990s of a technical innovation, the highly efficient combined-cycle gas turbine for power plants (GE’s explanation) – began a process whereby coal could no longer compete on price with natural gas for power generation.

New natural-gas-fired power plants were built, coal-fired power plants were retired. Demand for thermal coal collapsed, as did the price. Eventually all major coal mining companies filed for bankruptcy, a bunch of them twice. That was collateral damage of these billions of dollars of investor cash that kept flowing into fracking.

Surviving in this pricing environment for overleveraged permanently cash-flow negative companies in the fracking business has proven to be tough – and for investors, who kept buying their hype over the years, it has turned into a massacre.

Investors have not only poured billions of dollars into supplying these companies with debt capital – including the $262 billion listed in bankruptcy filings since 2015 – but also into supplying them with equity capital as these companies sold new shares to raise money, and these billions in equity capital have now disappeared without trace. Those billions from those share sales don’t even get mentioned in bankruptcy filings.