Whitty says Sage could have considered lockdown earlier – but also suggests proposing such radical policy job for ministers

The key charge against Prof Sir Chris Whitty, and Sage (the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies – the expert body he co-chaired) is that they should have considered the case for a lockdown much earlier than they did, and put that proposal to government. Hugo Keith KC put this argument to Whitty in the final minutes before the break. Whitty’s response was nuanced.

-

Whitty said it was “reasonable” to argue that Sage should have considered the case for a full lockdown earlier. When Keith first put his question, Whitty said that although restrictions had been imposed in the past in previous pandemics, full lockdowns had not been used. He went on:

The idea of essentially, by law, locking down all society is not something which had previously been used. You could argue, and I think it is reasonable to argue, that that is something we should have cottoned on to an earlier stage.

In reality, my view is that the band of situations where that would be relevant is in fact relatively narrow.

-

But Whitty also suggested that it was for government, not scientists, to propose such a radical intervention. He accepted that Sage had not considered the case for a lockdown in early and mid February.

Did Sage look in detail at a mandatory lockdown … in early and mid February? I think the short answer is no. That’s pretty clear from the minutes. We did, on the other hand, look at ways of keeping households separated.

Whitty said China had provided an example of a full lockdown approach. He went on:

You can argue that we should have gone for a maximalist model. I don’t want to put anyone into a difficult position, but were we to have been instructed by ministers, ‘what would happen if we did a Chinese approach?’, that would be something that Sage would undoubtedly have looked at.

The question actually, I think, is would it have been appropriate for a group of scientsts to come up with what I consider is quite a radical proposition to put to government? I think that’s a debatable question.

Key events

Whitty says he would like to see scientists advising government offered protection from legal action

Keith says he does not want to cover the disgraceful abuse directed at Sage scientists. But he asks if Whitty was concerned that scientists advising goverment might be open to some legal action.

Whitty says he is concerned about this. He says the legal position is not clear, because the advisers are not government employees. He says he would like to ensure that they get protection from legal claims. That should be “solvable”, he says.

Back at the hearing Hugo Keith KC, counsel for the inquiry, is getting to the point in early/mid-March 2020 when No 10 realised a new approach was needed.

Whitty accepts this was in response to the data changing. He says, in situations like this, data trumps modelling.

Vallance says Sunak was wrong to suggest Sage did not realise Treasury official listening to its meetings

Turning away from the hearing for a moment, Chris Smyth from the Times has found a passage in Sir Patrick Vallance’s lengthy witness statement (published by the inquiry last night) in which he seems to contradict something said by Rishi Sunak.

In an interview with the Spectator last summer Sunak claimed that Sage members did not realise the Treasury had an official listenting to their meetings. The interview took place during the Tory leadership contest and the interview was about Sunak’s scepticism about lockdown measures (also opposed by the Spectator).

Vallance, the Sage co-chair at the time, says the Treasury official attended Sage meetings because he actively encouraged it.

In his evidence yesterday Vallance also cast doubt on Sunak’s claim not to be aware of scientists’ concerns about his “eat out to help out” scheme.

Keith asks if it was realistic to expect Whitty and Patrick Vallance to relay to ministers the full extent of what experts were saying in Sage meetings.

Whitty says writing up the whole meeting would have taken too long.

But he says, because he and Vallance were both summarising what was said, that provided “some degree of error prevention” because, if one of them missed something out, the other could correct.

The hearing has resumed.

Whitty said that when Dominic Cummings was allowed to listen to Sage meetings, that caused a row. But Whitty said he personally thought this was a sensible arrangement.

UPDATE: Whitty said:

I thought it was perfectly sensible that if one of the most senior advisers to the prime minister, if she or he wished to, could listen in on Sage, struck me as a sensible thing to do … they could ask questions potentially, but try to bias the answer that was given and that would be extremely unacceptable, but that wasn’t the situation, in my view, that happened.

Whitty says Sage could have considered lockdown earlier – but also suggests proposing such radical policy job for ministers

The key charge against Prof Sir Chris Whitty, and Sage (the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies – the expert body he co-chaired) is that they should have considered the case for a lockdown much earlier than they did, and put that proposal to government. Hugo Keith KC put this argument to Whitty in the final minutes before the break. Whitty’s response was nuanced.

-

Whitty said it was “reasonable” to argue that Sage should have considered the case for a full lockdown earlier. When Keith first put his question, Whitty said that although restrictions had been imposed in the past in previous pandemics, full lockdowns had not been used. He went on:

The idea of essentially, by law, locking down all society is not something which had previously been used. You could argue, and I think it is reasonable to argue, that that is something we should have cottoned on to an earlier stage.

In reality, my view is that the band of situations where that would be relevant is in fact relatively narrow.

-

But Whitty also suggested that it was for government, not scientists, to propose such a radical intervention. He accepted that Sage had not considered the case for a lockdown in early and mid February.

Did Sage look in detail at a mandatory lockdown … in early and mid February? I think the short answer is no. That’s pretty clear from the minutes. We did, on the other hand, look at ways of keeping households separated.

Whitty said China had provided an example of a full lockdown approach. He went on:

You can argue that we should have gone for a maximalist model. I don’t want to put anyone into a difficult position, but were we to have been instructed by ministers, ‘what would happen if we did a Chinese approach?’, that would be something that Sage would undoubtedly have looked at.

The question actually, I think, is would it have been appropriate for a group of scientsts to come up with what I consider is quite a radical proposition to put to government? I think that’s a debatable question.

Q: In your witness statement you talk about Sage having a “failure of imagination” at the very start. What did you mean by that?

Whitty says he wanted Sage to consider the experience of other pandemics. He was aware of the danger of a second wave in winter. That is what happened in previous flu pandemics in the 20th century. That is something that was not in the modelling, but had happened in the past.

And he says, in the past, a lot of other NPIs (non-pharmaceutical interventions) had been used, such as self-isolation, quarantine and closing schools.

But full lockdowns had not been used, he says.

He says it is reasonable to argue that Sage should have considered.

Q: So if there was a failure to think about the prospect of a “mandatory stay-at-home order” being an option, if Sage had thought it was an option, would the government have considered it?

Whitty says, by the middle of March, Sage was saying the government would have to significantly reduce interactions by households. Whether or not to do that by law was a political decision.

He says this approach had been used in China.

Q: Should Sage have proposed a lockdown as an option?

Whitty says China “had thrown the kitchen sink at this”. He says his view was that the UK needed to find a way of cutting interactions.

He says you could argue that Sage should have gone for a “maximalist model”. He says if ministers had proposed that, they would have had a look at it.

But he says it is “debatable” whether Sage should have taken the initiative, he says.

And they are now stopping for a break.

Whitty says Sage was not the only route by which scientific advice was provided to government. It is important to stress that, he says. He says the government had many other sources of advice.

Q: In your witness statement, you says as co-chair of Sage you are likely to be biased in its favour. Were you aware of how other countries get scientific advice?

Whitty says he was well aware of how other countries do this.

In general, the UK system of integration of science into government is still short of where it should be, by “quite some distance”, but it is better than in some other countries, he says.

The Sage system “had some pluses and minuses”.

But he could not see another system that made him think “if only we had that, we would be in a much better shape”.

Q: There is a tension between having a body small enough to take decisions, but large enough to represent a wide range of views.

Whitty says, at first, it was too Sage. Patrick Vallance recognised that and responded. Arguable it later got too large, Whitty says.

He says it is important to stress Sage is not a fixed body. People come on to it and go off it, depending on what the problem is.

Whitty says the countries that could scale up testing quickly, like South Korea, had invested in that capacity. He says South Korea had had a bad experience with Mers.

For a country like the UK, it was much harder, he says.

Q: Were you consulted on the decision to disband Public Health England?

Whitty says he was just told this was happening. He thought PHE had acted professionally.

Whitty says the CMOs for England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland sometimes gave collective advice when they wanted to give a collective view on something important.

Q: Were there any significant scientific disagreements between you?

Not that he can recall, says Whitty.

But he says they sometimes had to think about things quite hard. Sometimes they were 49%/51% calls.

The most difficult decisions were about borders, he says.

Q: There have been claims there was not proper collaboration between the four nations.

Whitty says the CMOs, and the public agencies, did a lot together. And the presidents of the medical colleges worked together.

But, he says, that does not mean that at an operational and political level there weren’t differences.

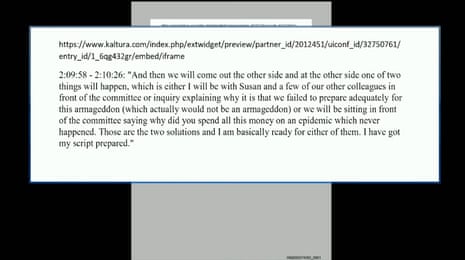

Keith asks Whitty about a comment he gave in a speech on 12 February 2020. He shows it to the inquiry.

Whitty defends what he was saying.

Keith says Whitty was talking about the risk of spending money on something that might not happen. He suggests that would be overreaction.

Whitty says the precautionary principle is often misunderstood.

Where there are no downsides, the precautionary principle justifies acting; for example, telling people to wash their hands.

But that does not apply in cases where acting does have downsides, he says.

Whitty says he does not accept that he warned against over-reacting at start of Covid inquiry

Whitty says doctors have to give advice on both sides of equation. If a patient needs an operation, even if a doctor thinks it is worthwhile, they have to give advice about the potential downsides, he says.

He suggests this influenced his thinking on advice about lockdown measures.

Q: To what extent did the need for data impact on your advice early on?

Whitty says, by the time Sage was giving advice, he was supporting the Sage advice.

From 16 March onwards, Sage was very clear about the need for action.

But, when you give advice, it is also important to acknowledge the downsides too, he says.

Q: There is a difference between accepting the downsides, and saying you should not overreact. Did you warn against overreacting?

Whitty says he was not deviating from the position of Sage.

The view of Sage was that, to avoid deaths, action was necessary.

But it was also clear that downsides would be involved.

He says ministers needed to know that. If they were not aware, there was a risk of them reversing course.

He says this approach was appropriate. Any doctor or civil servant would accept this was the correct thing to do.

Q: Did Sage itself warn against the dangers of overreacting from early January to early March?

Whitty says he does not think Sage would have used the phrase overreaction. It was about emphasising the downsides.

Q: The documentary evidence seems to suggest you were prominent in warning of the risk of overreacting. Is that fair?

Whitty says he rejects Keith’s characterisation of this as “overreaction” because that implies he thought the reaction should not happen. His concern was to make sure the downsides were understood.

I’ve rejected and I will continue to reject your characterisation of this as ‘overreaction’, because that implies that I thought that in a sense the action should not happen.

What I thought should happen is that people should be aware that without action very serious things would occur but the downsides of those actions should be made transparent.

I don’t consider that incorrect.

Whitty says he was wary of introducing Covid interventions too early because he knew poor people would lose out most

Q: Were you co-chair of Sage, or was Sir Patrick Vallance the lead chair?

Whitty says he and Vallance agreed that it was best to have a permanent chair. So Vallance chaired the meetings when he was there. But technically they were co-chairs.

Q: Did you try to form a common position on advice from Sage, and on technical advice to government?

Yes, says Whitty.

He says in one respect he was a member of Sage. He gave opinions in his own capacity.

But, once Sage had agreed a position, he saw it as his role to express the Sage position – not his own, personal view. Vallance also expressed the collective Sage view.

Q: Was it hard to ensure you were always singing from the same hymnsheet?

Whitty says the Sage process helped establish a common position. Where Sage did not consider a matter, he and Vallance tried to agree a common view before they advised the government.

Q: Was there a tension between you and Vallance? Jeremy Farrar said this in his book.

Whitty says Farrar, who is a colleague and a friend, had a book to sell. He says the differences between him and Vallance were small.

Q: Farrar in his book, and Vallance in his diary, say you were more cautious, and more inclined to wait until moving to measures.

Whitty says they should be “very careful of the narcissism of small differences”. The differences were very small.

But he was very clear that the impacts of measures such as cocooning (a precursor to lockdown) would be highest in areas of deprivation.

He says, with the benefit of hindsight, he thinks they went “a bit too late” in terms of introducing measures in the first wave.

He says he was probably further in the “let’s think through the disadvantages” camp as the impact of interventions was being considered.

UPDATE: Whitty said:

Well Sir Jeremy, who is a good friend and colleague, had a book to sell, and that made it more exciting, I’m told.

My own view was that actually the differences were extremely small

And the main one – and Sir Patrick, I thought put it very well – was that I saw as part of my role within Sage, in my first role as an individual, to reflect some of the very significant problems for particularly areas of deprivation, I saw for many years the actions that we were taking in terms of what was going to be advised to ministers to consider for what they did next.

And that I think that was an appropriate thing for me to do and Sir Patrick also thought it was appropriate.

Q: Did the system of international collaboration work well?

Whitty says, in the circumstances, it worked as well as could be expected.

Q: Can you give examples?

Whitty says, for every new wave of Covid, the first information came from the countries involved.

And he says, with the original Wuhan wave, they at first relied on Chinese science.

There were many groups. But they all involved sharing information.

When the UK had the Alpha wave (called the Kent variant at the time), it was the UK sharing its information with other countries.